Luther Visualized 14 – Augsburg Confession

October 23, 2017 Leave a comment

The Augsburg Confession

Left: Lucas Cranach the Elder, Elector John the Steadfast of Saxony, oil on panel, c. 1533; housed in the National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen. Right: Lucas Cranach’s Studio, Philipp Melanchthon, oil on panel, 1532; housed in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden.

Around 3 p.m. on Saturday, June 25, 1530, Ferdinand, King of Hungary and Bohemia, and all the other electors, princes, and imperial estates assembled before Holy Roman Emperor Charles V “in the large downstairs room” or chapter hall of the episcopal palace in Augsburg, where the emperor was lodging for the duration of the diet he had convened that year. The Saxon chancellor Christian Beyer stepped forward with the German copy of the confession that Philipp Melanchthon (pictured above right) had prepared and that seven princes and representatives of two free imperial cities had signed. The chancellor read it “so clearly, distinctly, deliberately, and with a voice so very strong and rich that he could be clearly heard not only in that very large hall, but also in the courtyard below and the surrounding area.” It took him two hours to finish, and his copy and a Latin copy were then handed over to the emperor.

Because of how the Romanists received the confession, its presentation subsequently came to represent the birthday of the Lutheran Church and the official split from the Roman Catholic Church. Confessional Lutheran churches and church bodies still subscribe to its doctrine without qualification today. It covers a wide range of subjects from God to original sin to justification to the sacraments to free will to monastic vows. (You can read it online here.) Martin Luther, writing from the Coburg Fortress, where he stayed for the duration of the diet since he was still an outlaw, commented on an early draft of the confession, “It pleases me quite well and I know nothing to improve or change in it, nor would it work if I did, since I cannot step so gently and softly.”

The princes and representatives who signed the confession are as follows:

- John, Duke of Saxony, Elector (pictured above left)

- George, Margrave of Brandenburg

- Ernest, Duke of Lueneberg

- Philip, Landgrave of Hesse

- John Frederick, Duke of Saxony (the son of Elector John; regarding the high esteem in which he held the confession, see here)

- Francis, Duke of Lueneberg

- Wolfgang, Prince of Anhalt

- The City of Nuremberg

- The City of Reutlingen

Sources

Georg Coelestin, Historia Comitiorum Anno M. D. XXX. Augustae Celebratorum (Frankfurt an der Oder: Johannes Eichorn, 1577), fol. 141

Dr. Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette, ed., Dr. Martin Luthers Briefe, Sendschreiben und Bedenken, vierter Theil (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1827), p. 17

Carolus Gottlieb Bretschneider, ed., Corpus Reformatorum, vol. 2 (Halle: C. A. Schwetschke and Son, 1835), cols. 139ff, esp. col. 142

Theodor Kolde, Historische Einleitung in die Symbolischen Bücher der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche (Gütersloh: Druck und Verlag von C. Bertelsmann, 1907), pp. xix-xx

Hans Lietzmann, Heinrich Bornkamm, et al., eds., Die Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche, 2nd ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1955)

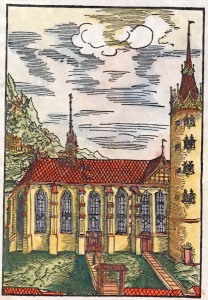

Augusta iuxta figuram quam hisce temporibus habet delineata, woodcut, 1575 (coloring subsequent), based on Hans Rogel, Des Heiligen Römischen Reichs Statt Augspurg, woodcut, 1563

This famous bird’s-eye view woodcut of Augsburg by Hans Rogel was published in Georg Braun’s Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Antwerp: Aegidius Radeus, 1575). It is oriented with west on top. #105 marks the palace of the prince-bishop, where the Augsburg Confession was presented, just west of the Cathedral of Our Lady (#32). Only the tower from the original palace remains today, attached to a late-Baroque style building that now houses government offices for the district of Swabia. A single plaque on the outside of this building is the only tribute to the presentation of the Augsburg Confession. It reads:

Hier stand vordem die bischöfliche Pfalz in deren Kapitelsaal am 25. Juni 1530 die CONFESSIO AUGUSTANA verkündet wurde.

This is where the episcopal palace once stood, in whose chapter hall the AUGSBURG CONFESSION was delivered on June 25, 1530.