Luther Visualized 4 – The 95 Theses

August 23, 2017 Leave a comment

Luther Posts the Ninety-Five Theses on Indulgences

Anonymous, Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony’s Dream in Schweinitz on October 31, 1517, 1717, woodcut.

This scene, itself a recasting of an earlier one from 1617, depicts a later tradition (dating to 1591), supposedly related thirdhand, that, on the night before Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Elector Frederick the Wise had a dream which he related to his brother John the following morning. In the dream, a monk wrote something on the door of his Castle Church with a pen whose quill stretched all the way to Rome and threatened to knock the tiara from the pope’s head. (UPDATE: See this post for more on Elector Frederick’s dream.)

Source

Johann Georg Theodor Gräße, Der Sagenschatz des Königreichs Sachsen (Dresden: Verlag von G. Schönfeld’s Buchhandlung, 1855), pp. 29-32

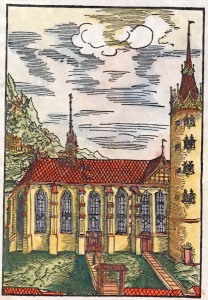

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Church of the Foundation of All Saints (Castle Church), woodcut, 1509 (coloring subsequent)

On the evening of October 31, 1517, Martin Luther nailed his Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. Or did he? Philipp Melanchthon was the first to report on the posting of the theses as we commonly depict it, but he was not in Wittenberg in 1517 and he didn’t report on the posting of the theses until after Luther’s death. The closest report we get that may have been recorded during Luther’s lifetime is a handwritten note by Georg Rörer in a 1540 copy of the New Testament that was also used by Luther for making translation revisions, but that note says that Luther posted his theses on October 31 on the doors of both churches in Wittenberg. Plus, Rörer later wrote another note that matched Melanchthon’s information, apparently after he had read Melanchthon’s account. We do know that Luther included a copy of the theses with a letter to Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz on October 31, and that he himself reckoned the “treading underfoot” of indulgences from that day, but his own correspondence from 1518 seems to imply that he did not immediately make the theses public. Historian Martin Brecht suggests that Luther did not post the theses until perhaps the middle of November 1517. (UPDATE [4/25/20]: Andrew Pettegree makes a good case that Luther did in fact post the theses on October 31 based on publishing evidence [Brand Luther, 12–13, 70–72, 76].) This woodcut of the Castle Church appeared in Das Wittenberger Heiltumsbuch of 1509, which depicted Elector Frederick the Wise’s extensive relic collection and was illustrated with numerous woodcuts by Lucas Cranach. In 1760 the Castle Church, including the wooden doors on which Luther had allegedly posted the theses, was destroyed by fire. In 1858 commemorative bronze doors inscribed with the original Latin theses were mounted where the old wooden doors stood.

Sources

Philipp Melanchthon’s preface to Tomus Secundus Omnium Operum Reverendi Domini Martini Lutheri, Doctoris Theologiae, etc. (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1546), par. 24 (third par. on the linked page)

Volker Leppin and Timothy J. Wengert, “Sources for and against the Posting of the Ninety-Five Theses,” Lutheran Quarterly, vol. 29 (Winter 2015), pp. 373-398

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: His Road to Reformation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1985), pp. 190-202