Luther Visualized 7 – Trial and Excommunication

September 5, 2017 Leave a comment

The Papal Bull Threatening Luther’s Excommunication

Manuscript of the papal bull Exsurge Domine in which Luther is threatened with excommunication (Vatican Secret Archives, Reg. Vat., 1160, f. 251r)

This is a manuscript of the infamous papal bull (edict) threatening to excommunicate Martin Luther, proclaimed on July 24, 1520. It begins:

Leo etc. For future memory of the matter. Arise, O Lord, and judge your cause. Recall to memory your reproaches of those things that are perpetrated by senseless men all day long. Bend your ear to our prayers, for foxes have arisen seeking to demolish the vineyard whose winepress you alone have trodden. … A wild boar from the forest is endeavoring to destroy it…

Luther had sixty days from September 29 to send a certified retraction of his errors to Rome. Instead, on December 10, Luther appeared with the bull, trembling and praying, before a pyre lit in the carrion pit at Holy Cross Chapel outside the eastern gate of Wittenberg. He cast the bull into the fire with the words, “Because you have confounded the Holy Place [or truth] of God, today he confounds you in this fire [or may eternal fire also confound you]. Amen.”

Pope Leo X issued the actual bull of excommunication, Decet Romanum Pontificem (It Is Proper for the Roman Pontiff), on January 3, 1521.

Sources

Vatican Secret Archives, “The Bull Exsurge Domine by Leo X with Which He Threatens to Excommunicate Martin Luther”

Weimarer Ausgabe 7:183ff

Max Perlbach and Johannes Luther, “Ein neuer Bericht über Luthers Verbrennung der Bannbulle,” in Sitzungsberichte der königlich preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin, 1907), 1:95ff

Luther’s Works 48:192

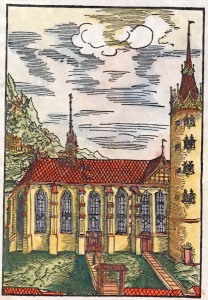

The Vineyard of the Lord

Lucas Cranach the Younger, The Vineyard of the Lord, oil on panel, 1569, on the grave slab for Paul Eber in the Wittenberg Parish Church (photo by the Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt).

(Updated on 1/22/21:) When Paul Eber (8 Nov 1511—10 Dec 1569) was thirteen, his horse bolted, throwing him from the saddle and dragging him along on the ground for half an hour, leaving him somewhat crooked for the rest of his life. He went on to be professor of Latin at the University of Wittenberg (1541), head preacher at the Castle Church (1557), head pastor of the City Church and general superintendent of the district (1558), and the most influential hymn writer of the Reformation after Luther. When he died, his children commissioned an epitaph from Lucas Cranach the Younger, who chose a vineyard as the theme of the accompanying painting (pictured), which is still on display in the City Church (St. Mary’s) in Wittenberg. In the right-hand foreground of the painting, Eber and his family, including thirteen children, are kneeling at the fence on the right hand side. Eber, whose name means “wild boar” (from the Latin aper meaning the same), is holding an open Bible; he had been responsible for revising the translation of the Old Testament in the Latin Bible, since he was also an Old Testament professor. In the vineyard itself, the following figures can be identified (Rhein, 193):

In the foreground, Luther, Melanchthon, and Bugenhagen form a prominent triangle, which is extended by the vine-pruning Eber in front of them [thus Eber is depicted twice in the painting]. … Melanchthon is drawing water from a well to irrigate the soil, that is to say, he goes ad fontes, to the sources, the three holy languages of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin… Bugenhagen, finally, is hoeing the soil, thus establishing order in a way similar to his church orders… Other historical figures can be recognized next to those mentioned: Johannes Forster, who is watering the soil; Georg Major, who is tying the vines; Paul Krell, who is carrying the grapes away in a tub; Caspar Cruciger, who is driving a rod into the ground; Justus Jonas, who is digging the soil with a spade; Georg Spalatin, with a muck shovel; Georg Rörer, who is picking up stones; and Sebastian Fröschel, who empties the stones from a trough.

These men labor faithfully in the Lord’s vineyard, while the pope and his cardinals, bishops, monks, and nuns do their best to ruin the vineyard.

For more on this painting, read here. See also Stefan Rhein, “Friends and Colleagues: Martin Luther and His Fellow Reformers in Wittenberg,” in Martin Luther and the Reformation (Dresden: Sandstein Verlag, 2016), 192–98.