Luther’s Sermon on the Authority of St. Peter

August 5, 2023 Leave a comment

Translator’s Preface

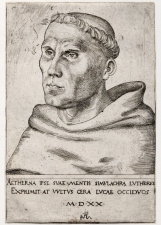

Martin Luther preached the following sermon on June 29, 1522, which was both the Second Sunday after Trinity and the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. Since there was usually a morning and an afternoon sermon on a typical Sunday, and since the morning sermon was usually reserved for the regularly appointed Gospel, Martin Luther probably preached this sermon on the special Gospel for the feast day in the afternoon. We do not know who transcribed it; Georg Rörer, the eventual tireless transcriber of Luther’s sermons, didn’t arrive in Wittenberg until the fall of 1522. But the transcription was quickly converted into two printed German pamphlets, one published in Augsburg and the other in Nuremberg. When translated, both pamphlets were titled (with slightly different German spellings): “A Christian Sermon on the Authority of Saint Peter, Delivered by Martin Luther in Wittenberg in the Twenty-Second Year. Very Useful for All Believers in Christ to Know.” These pamphlets are the primary basis of the sermon’s reproduction in the Weimar Edition of Luther’s works (see Sources below).

This sermon was also included in three later collections—Johann Schott’s collection of twelve Luther sermons on several Marian festivals and other saints’ festivals (XII. Predig D. Martin Luthers, Strasbourg, 1523), Johann Herwagen’s similar collection of “short sermons” translated into Latin (Conciunculae quaedam, Strasbourg, 1526), and Stephan Roth’s collection of Luther’s festival sermons now commonly called Roth’s Festival Postil (Auslegung der Euangelien an den furnemisten Festen ym gantzen iare, Wittenberg, 1527). Roth’s is the most edited version, but he also corrected some of the typographical errors in the earlier printings.

In the broader context, Luther had just returned from the Wartburg less than four months earlier, and he was busy. He began a May 15 letter to Spalatin by complaining about how overwhelmed he was with all the letters he had to read and reply to. He was also in the throes of overseeing the publication of his New Testament translation. The printing of Matthew had been completed by the beginning of June, and Luther had included this marginal note on 16:18 (“And I also say to you: You are Peter”): “Cephas in Syriac and Petros in Greek mean eyn fels [“a rock”] in German, and all Christians are Peters on account of the confession of faith that Peter makes here, which is the rock on which Peter and all Peters are built. If we share his confession, then we also share his name.” Luther was still in the process of reconciling the basic tenets of the Reformation, which he had gleaned from Scripture, with Scripture passages that had been used for many years to promote and uphold important Roman Catholic teachings.

In the new Christian Worship three-year lectionary, the text Luther based this sermon on is the appointed Gospel for Sundays falling on August 21–27 in Year A (Proper 16). I pray that this fresh translation proves professionally beneficial for my fellow confessional Lutheran pastors, and spiritually edifying and historically instructive for all. It is indeed a “very useful [sermon] for all believers in Christ to know.” To God alone be the glory.

Sermon on the Authority of Saint Peter

Matthew 16:13–19.

Then Jesus came into the region of the city of Caesarea Philippi and asked his disciples, “Who do the people say that the Son of Man is?” They said, “Some say you are John the Baptist, others that you are Elijah, still others that you are Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” He said to them, “And who do you say that I am?” Then Simon Peter answered, “You are Christ, the Son of the living God.” And Jesus replied to him, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah. Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father in heaven. And I also say to you: You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my congregation, and the gates of hell shall not overcome it. And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven. All that you will bind on earth shall also be bound in heaven, and all that you will loose on earth shall also be loosed in heaven.”

You know this Gospel well, for it has now been preached and hyped for so long that by now it should be very well known. And it is also basically the best section and the chief passage in the Gospel that Matthew records. And they1 have been using this passage to ornament themselves from the beginning, and so there is also no passage that has caused greater damage than this one, which is what happens when those who are reckless meddle with the Scriptures. They twist them this way and that, which is exactly what has happened, and the holier the passage is, the sooner a person can go wrong and the more shameful the damage he can do. Therefore observe this as a general rule: Whenever anyone goes along and floats and hovers around in the Scriptures like this, and has no firm understanding on which he can establish his heart, he should just leave it alone entirely, for when the devil has caught you with his pitchfork, so that you are not established on a settled conscience like you should be, he tosses you back and forth, so that you don’t know which way is out. Therefore you must be certain on the basis of a clear and pure understanding.

This Gospel is all about making us recognize what Christ is. Now Christ is recognized in a twofold way. The first way is by his life, as is said here: “Some say you are Elijah, others John the Baptist, still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” Thus when a person judges by reason alone, and by flesh and blood, he cannot grasp Christ any further than merely as a holy, pious man who provides others with a fine example that they should follow. Reason cannot understand him any further, even if he were to show up here today. Now whoever accepts him this way, merely as an example of a good life, is still locked out of heaven. He has not yet grasped or recognized Christ. He thinks of him only as a holy man as Elijah once was. Therefore note the rule: Where reason alone is involved, there you will only find the understanding that people think of him as a teacher and holy man. That perception will last as long as the heavenly Father does not instruct that person’s heart.

The second understanding of Christ is the one that St. Peter expresses: “You are a special man, not Elijah, not John, not Jeremiah, not someone who shows and leads the way for other people. There needs to be something much higher with you. You are Christ, the holy Son of God.” This identification cannot be attributed to any saint, whether John or Elijah or Jeremiah or any one of the prophets. Therefore when someone thinks of Christ only as a pious man, his reason always continues to float and hover around, going from one identification to the next, from Elijah to Jeremiah. But here he is singled out and held to be something more special than all the saints, and something definite and certain. For if I am uncertain about Christ, my conscience is never at peace and my heart does not have any rest. Therefore a distinction is being made here between faith and works. Here Christ himself is making it clear to us how we should grab hold of him—not with works. We do not come to him with works; works come after the fact. I must first come into the possession of his goods and blessings, so that he becomes mine and I become his.

Christ makes it clear that this is what he wants when Peter says, “You are Christ, the Son of the living God.” Christ himself acknowledges this answer when he says, “Blessed are you, Simon Peter. Your flesh and blood has not revealed this to you. And you are Peter, and a rock, and on this rock I will build my church, which the gates of hell shall not overcome.” Now here is where the power lies to know what the church is, what the rock is, and what it means to build the church. Here we must find an enduring rock on which the church is supposed to stand, just as he says: It is a rock on which my church shall stand, and the gates of hell will not overcome it. This rock is Christ, or the Word, for Christ is not known except through his word. Without his word, Christ’s flesh does not help me at all, even if it were to show up here today. And it is these words, when it is said that Christ is the Son of the living God, that make him known to me and describe him for me. This is what I build on. These words are so certain, so true, so established, that no other rock can be so surely and strongly grounded and fortified.

Now “rock” means nothing else but the evangelical Christian truth that proclaims Christ to me, by which I establish my conscience on Christ. No authority or power, not even the gates of hell, shall be able to do anything against this rock, as Paul says in 1 Corinthians 3[:11], “No one is able to lay any foundation other than the one already laid, which is Jesus Christ.” The same thing is said by Isaiah in Chapter 28, which is really what Christ is commenting on here: “I will lay a stone in Zion, an approved stone, a precious stone, one that is well anchored, so that whoever believes in him will not be put to shame” [28:16]. The apostles make very powerful use of this passage and it is also cited in 1 Peter 2[:6] and in Romans [9:33 and] 10[:11]. There you have it in clear words that God plans to lay one foundation stone, one keystone,2 an approved stone, a cornerstone, and none other besides, which is Christ and his gospel. Whoever is established on this stone will not be put to shame and will stand so firmly that all the gates of hell shall not overcome him.

Therefore Christ alone is the rock, and wherever someone lays down a different rock, make the sign of the cross and guard yourself, for that is certainly the devil. For this passage may not be understood about anyone else except Christ alone, as St. Paul says. That is the pure understanding of this passage, and no one can deny it. The universities do not deny it either; they admit that Christ is the rock. But they want St. Peter to be another rock next to him and try to lay an additional stone there. They want to create a dead-end path3 alongside the proper highway. We should not and will not tolerate that, for the more precious the passage is, the more firmly we should stand on it, for it is clear from Isaiah and Paul that Christ alone is the stone.

Now this is the understanding they have given to the passage: Christ says, “You are Peter. On this rock I will build my church.” They want to take that to mean that Peter is the rock, and all the popes who have succeeded him. So then they have to have two rocks. But that cannot be, since Peter singles Christ out here and will not let either John the Baptist or Elijah or Jeremiah be his equal. He does not want any of them to be the rock here. Plus, the pope is sometimes an evil scoundrel [böser bub] and nowhere near as good as St. John the Baptist or Elijah or Jeremiah. And if I cannot build on John, Jeremiah, Elijah, or any of the saints, how then am I supposed to build on a sinner whom the devil has possessed?

For this reason Christ tears all saints away from our eyes here, even his own mother. He wants there to be one rock, while they want to have two. Now either they must be lying or Scripture is. But if Scripture cannot lie, we must therefore conclude that the entire papal government is built on nothing but puddlework, lies, and blasphemy of God, and the pope is the arch-blasphemer of God by applying this passage to himself, even though it is only talking about Christ. The pope wants to be the stone, and the church is supposed to stand upon him, just as Christ foretold of him in Matthew 24[:5]: “Many will come in my name saying, ‘I am Christ.’” In so doing the pope makes himself out to be Christ. Sure, he does not want to have the name Christ, for he does not say, “I am Christ.” But he wants to attribute to himself the nature and the office that belong only to Christ.

Now this is the simple understanding of this passage: Christ is the foundation stone upon which the church shall stand, so that no authority or power will be able to do anything against her. It’s just like when a house is built here on earth, it relies entirely on its good footing, or like a castle that has its foundation on a rock. We could imagine the castle saying, “I have a good foundation, and I completely depend on it.” The heart that stands upon Christ does the same thing. It says, “I have Christ, God’s Son. I stand here upon him and I completely depend on him as on a well-anchored rock. Nothing can harm me.”

Therefore to build on the rock here means nothing else but to believe in Christ and to confidently rely on him, trusting that he is mine along with all his goods and blessings. For I stand upon all that he has and is capable of. His suffering, his dying, his righteousness, and all that is his is also mine. That is what I stand on, just like a house upon a rock, which stands on all that the rock is capable of. Now when I stand on him the same way and know that he is God’s Son, that his life is greater than all death, his honor greater than all shame, his blessedness greater than all sorrow, his righteousness greater than all sin, and so on, then nothing can do anything against me, even if all the gates of hell were to come at once.

Now on the other hand, when I stand on anything else besides this foundation stone, such as on some good work, and even if I had the works of all the saints, yes, even of St. Peter, and do not have faith, then I am opposed to Christ. For compared to his light, everything else is darkness; compared to his wisdom, everything else is foolish; compared to his righteousness, everything else is sin. Now when I stand on my own work and run up against him through his judgment, I would be knocked down into eternal damnation. But when I grab hold of him and build on him, then I am taking hold of his righteousness and all that is his, which preserves me before him so that I am not put to shame. Why can I not be put to shame? Because I am built on God’s righteousness, which is God himself. He cannot reject that, otherwise he would be rejecting himself.

This is the correct, simple understanding of this passage. Therefore do not let yourselves be led away from this understanding, otherwise you will be knocked down and condemned by the rock.

Now they may say, “But Christ says here, ‘You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church.’” You have to understand that this way: Here Peter is called a rock, and Christ is called a rock elsewhere, because Christ is the whole rock, while Peter is a part of the rock. It’s like how he is called Christ, while we are called Christians after him, by reason of fellowship and faith, since we also have a Christ-like nature in us. For through faith we become one spirit with Christ and receive from him his nature. He is pious and holy, he is righteous, and we are righteous through him, and all that he has and is capable of, we may boast of too. But this is the difference: Christ has all his goods by obligation and by right, while we have them by grace and mercy. In the same way he calls Peter a rock here, because he stands on the rock and through him becomes a rock himself. Thus we too are rightly called Peters, that is, rocks, because we acknowledge the rock, Christ.

Now they may wish to press the matter further and say, “Whatever the case may be with your interpretation, I am going to follow the text, which says, ‘You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church.’ There the text indicates that Peter is the rock.” If so, then confront them with what follows, namely that all the gates of hell shall not be able to do anything against this rock. St. Peter did not stand firm, for immediately in the text that follows the Lord called him a devil. The Lord was saying how he would go to Jerusalem, would suffer so much at the hands of the Jews, and would ultimately also be put to death and then rise again. When he said that, Peter spoke up and rebuked the Lord, “God forbid such a thing! This shall never happen to you.” Then the Lord said, “Get behind me, you devil or tempter!” [Matt. 16:21–23]. So the rock would have fallen and the gates of hell would have overcome it, if the church were built on Peter. For the Lord continues by saying, “Peter, you do not have the will that God has” [16:23]. See, my friend? Do you see? Here the Lord calls Peter a devil, when he previously pronounced him holy and blessed. Why? All of this happened so that he would stuff the yappers of the useless babblers who want to have the church built on Peter and not on Christ himself. He also had it happen in order to make us certain in our understanding, so that we would know that the church was not founded on a puddle or a manure pile, but on Christ, who was established as a cornerstone, as a foundation stone that is well anchored, as Isaiah says.

Likewise when the servant girl called out to Peter and he denied Christ [Mark 14:66–72], when he then falls and I am standing on him, where will I end up? If the devil were to take the pope captive and I were standing on him, I would definitely be on bad footing. That is why Christ also let Peter fall, so that we would not regard him as the rock and would not build on him. For we must be established on the One who stands firm against all devils, which is Christ. Therefore hold firm on this understanding, for he says that all the gates of hell shall be able to do nothing against it.

Faith is an almighty thing, like God himself is. That is why God also wants to authenticate and test it. That is also why everything that the devil has the power and ability to do must set itself against it, for Christ is not speaking empty words when he says here that all the gates of hell will not overcome it. “Gates” in Scripture mean a society and its government, since they would conduct their legal affairs by the gates, as God had commanded in the law in Deuteronomy 16: “You shall appoint judges and officials in all your gates” [16:18]. So here “gates” means every authority in the devil’s control, along with their attendants and followers,4 such as kings and princes, along with the wise men of this world, who cannot help but set themselves against this rock and this faith.5 The rock stands in the middle of the sea, where the waves roll along and storm, flash, bluster, and rage against it, as if they were trying to knock the rock over, but it has no problem standing firm, because it is well anchored. In the same way we must be alert and on our guard, because the devil and every authority in his control will charge at us and try taking on the rock. But he will not be able to do anything, just like the waves on the sea do not succeed in knocking the rock over, but fall away and break themselves up on it. It’s just like you see currently: Our ungracious princes are angry, and the highly learned are also angry, along with all those this world considers holy. But you should not pay any attention to it or waste any concern on it, for they are the gates of hell and the waves on the water that storm against this rock.

Christ continues: “And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven. All that you will bind on earth shall also be bound in heaven, and all that you will loose on earth shall also be loosed in heaven.” As you stuck with the simple understanding before, stick with it now, too. The keys are given to the one who stands on this rock through faith, to whomever the Father has given the ability to do so. Now you cannot single out any one person who remains standing on the rock, for one person falls today, the next one tomorrow, just as St. Peter fell. Therefore there is no specific individual to whom the keys belong. Instead they belong to the church, that is, to those who stand on this rock. The Christian church alone has the keys and no one else, although the pope and bishops could use them as those to whom their use has been entrusted by the congregation. A parson who carries out the ministry of the keys, that is, who baptizes, preaches, and administers the Sacrament, does so not on his own behalf but on behalf of the congregation. For he is a servant or minister of the entire congregation, to whom the keys have been given, even if he happens to be a scoundrel. For if he does it in place of the congregation, then the church is doing it, and if the church is doing it, then God is doing it. For you have to have a servant or minister. If the entire congregation all came forward and all baptized, they might very well drown the child, since there would probably be a thousand hands reaching for it. It won’t work. Therefore you have to have a minister who carries it out in place of the congregation.6

Now the keys to bind or to loose are the authority to teach and not just to absolve. For the keys are applied to everything by which I can help out my neighbor—to the comfort that one person gives another, to public and private confession, to absolution, but most commonly to preaching. For when a person preaches, “Whoever believes will be saved,” that is what it means to unlock, and when he preaches, “Whoever does not believe is condemned” [Mark 16:16], that is what it means to lock and bind.

The binding is put before the loosing. When I preach to someone, “You belong to the devil indoors and out [wie du geest und steest],” then heaven is closed to him. When he then falls down and acknowledges his sin, then I say, “Believe in Christ and your sins will be forgiven for you.” That is what it means for heaven to be unlocked, just like Peter does in Acts 2[:37–41]. Thus we all have the Christian authority to bind and lock and to loose and unlock.

Now the way they have applied it is to strengthen and establish the pope’s laws. They claim that binding means to make laws. But that is the way that blind guides go. But you should stick with the simple understanding that you have now heard and not let yourselves be turned away from it, if you want to stand firm against the attacks of sin, death, and the devil.

That is where we will let the matter rest for now and call upon God for his grace.

Sources

Pietsch, Paul, Georg Buchwald, Alfred Götze, et al., eds. Dr. Martin Luthers Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Vol. 10. Part 3. Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1905. Pages xvi, xxi, xliv, cxxvii–cxxix, 208–216.

I also consulted Stephan Roth’s version in his Festival Postil, as reproduced by Karl Drescher, Ernst Thiele, Georg Buchwald, et al., eds., Dr. Martin Luthers Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe, vol. 17, part 2 (Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1927), 446–53. Roth was especially useful in correcting some typographical errors in previous editions, providing alternate and better spellings of certain words, and filling out the end of Luther’s sermon, which is quite abrupt in the original pamphlets.

Endnotes

1 A few times in this sermon Luther uses a general “they” to refer to the papists.

2 German: hauptsteyn. In English, keystone denotes the central stone at the summit of an arch, but Luther is using it here as a synonym for cornerstone, but with emphasis on its vital importance.

3 German: holtzweg. A Holzweg, lit. “wood or timber path,” is a road or path in the woods that does not connect two inhabited locations, but leads only to a place where trees are being felled or some other commercial venture is being undertaken. The German expressions “to be or get on the Holzweg” mean “to be on the wrong track or to fall into error.”

4 Alternate translation: all the authority of the devil and those who follow it.

5 In his 1522 editions of the New Testament, Luther included this marginal note on “gates of hell” in Matthew 16:18: “The gates of hell are every authority opposed to Christians, such as sin, death, hell, worldly wisdom and power, etc.”

6 The Erlangen Lutheran theologian Johann Wilhelm Friedrich Hoefling (1802–1853) is caricatured as having a purely functional or practical view of the holy ministry, of which the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod has also been accused in the past. This position is defined thus: The holy ministry does not arise from divine institution, but from an inner, practical necessity of the church. It is easy to see how someone could find support for this position from Luther here, but Luther’s other writings on the holy ministry must also be taken into account. However, Luther certainly is underscoring here that order in the church is a reason for the existence of the public ministry, even if it is not the only or primary reason. Recall that the apostle Paul’s appeal to order among the Corinthians (1 Cor. 14:33, 40) was not simply phrased in human or practical terms. He rather appealed to the fact that God, who is a God of peace and order, wants peace and order to reign in his church.