Luther Visualized 18 – Physical Appearance

November 25, 2017 Leave a comment

Martin Luther’s Physical Appearance

Luther historian E. G. Schwiebert wrote that Lucas Cranach’s “zeal in reproducing the Reformer outstripped his talent,” and called it “most regrettable” that Luther was never sketched or painted by a more talented artist like Albrecht Dürer or Hans Holbein the Younger (p. 571). However, while Cranach’s reproductions are not exactly photographic, he and the members of his studio were certainly not lacking in skill.

Apart from Cranach’s reproductions of the man, which began in 1520, there was, to our knowledge, only one earlier depiction of him, an anonymous woodcut (#9 below) on the title page of Ein Sermon geprediget tzu Leipßgk uffm Schloß am tag Petri un pauli ym .xviiij. Jar / durch den wirdigen vater Doctorem Martinum Luther augustiner zu Wittenburgk (A Sermon Preached at the Castle in Leipzig on the Day of Sts. Peter and Paul in the Year [15]19 by the Worthy Father, Doctor Martin Luther, Augustinian in Wittenberg), printed by Wolfgang Stöckel in Leipzig. Both this woodcut, originally printed in reverse, and another anonymous woodcut, not included in this post, are consistent with Schwiebert’s assertion that for “the first thirty-eight years of his life [up until 1521] he was extremely thin” (p. 573). The latter woodcut is consistently depicted but erroneously cited in Luther biographies (e.g. Schwiebert, p. 574, where he calls it the “earliest known likeness” without citation or proof, and Brecht, vol. 1, p. 412, where he gives an erroneous source, as evidenced from the actual source he cites, whose woodcut is based on #1 below).

As for the reproductions originating with Cranach and his studio in Wittenberg during Luther’s lifetime (#8 excepted), they can be classified into 8 groups (medium and year[s] that the depictions originated and flourished in parentheses):

- Luther the Monk (copper engraving, 1520; variously copied and embellished by a number of artists)

- Luther the Doctor of Theology (paintings, c. 1520; copper engraving, 1521)

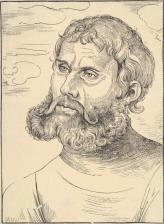

- Luther as Junker Jörg (paintings and woodcut, 1521-1522)

- Luther the Husband (paintings, 1525 & 1526)

- The Classic Luther (paintings, 1528-1529)

- Luther the Professor (paintings, 1532-1533)

- Luther the Aging Man (paintings, 1540-1541)

- Luther on His Deathbed (painting based on Lukas Fortennagel’s sketch of the dead Luther, 1546)

The other three visual depictions included below are the already mentioned anonymous woodcut (#9), a sketch of Luther lecturing by Johann Reifenstein (#10), and Fortennagel’s already mentioned painting (#11). Scroll down beneath the engravings, woodcuts, and paintings for more on Luther’s appearance.

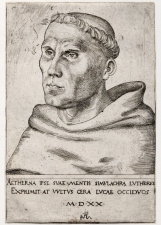

1. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk, copper engraving, 1520. The caption reads: “The eternal images of his mind Luther himself expresses, while the wax of Lucas expresses the perishable looks.”

2. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther with Doctor’s Cap, copper engraving, 1521. The caption reads: “The work of Lucas. This is a transient depiction of Luther; the eternal depiction of his mind he himself expresses.”

2. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk with Doctor’s Cap, oil on panel, c. 1520 (erroneous “1517” in the upper left-hand corner); housed in a private collection. These paintings circa 1520 are lesser known and therefore both are included here.

2. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther, oil on panel, c. 1520, since transferred to canvas; housed in the Lutherhaus Museum in Wittenberg.

3. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther as Junker Jörg [Squire George], oil on beechwood, 1521-1522; housed in the Weimar Classics Foundation. Martin Luther likely posed for this painting during his secret trip to Wittenberg in the first half of December 1521, but cf. next image.

3. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther as Junker Jörg, woodcut, 1522. The Latin superscription accompanying this woodcut read: “The image of Martin Luther, portrayed as he appeared when he returned from Patmos [Luther’s own biblical nickname for the Wartburg Castle] to Wittenberg.”

4. Lucas Cranach, Portraits of Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora, oil on beechwood, 1525; housed in the Basel Art Museum.

4. Lucas Cranach’s Studio, Portraits of Martin Luther and Katharina von Bora, oil on beechwood, 1525-1526; housed in the LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster.

5. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther, oil on panel, 1528; housed in the Art Collections of the Veste Coburg. Cf. the similar painting in the Lutherhaus Museum.

6. Lucas Cranach, Martin Luther, oil on beechwood, 1533; housed in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. The prototype for this painting, done on parchment in 1532 and housed in Drumlanrig Castle in Thornhill, Scotland, is one of Cranach’s boldest and finest depictions of Luther.

7. Lucas Cranach’s Studio, Martin Luther, oil on panel, c. 1541; housed in the Lutherhaus Museum, Wittenberg.

8. Lucas Cranach’s Studio, Martin Luther on His Deathbed, oil on oak, 1546; housed in the Lower Saxony State Museum, Hanover. See commentary above.

10. Johann Reifenstein, Luther lecturing in the classroom, sketch, 1545. The inscription was added in 1546 by Melanchthon. It begins with oft-quoted words of Luther: “While alive, I was your plague; when I die, I will be your death, O pope.” After some obituary-esque information, it concludes: “Even dead, he lives.”

While Cranach did have a virtual monopoly on Luther with regard to visual depictions, there are also written depictions that help us to complete our image of the man. Schwiebert gives the most complete treatment on the subject that I have read:

Vergerio, the papal nuncio, noted that Luther had a heavy, well-developed bone structure and strong shoulders… The Swiss student Kessler accidentally met Luther at the Hotel of the Black Bear in Jena when Luther was returning to Wittenberg from the Wartburg, still dressed as a knight. Kessler wrote in his Sabbata that Luther walked very “erect, bending backwards rather than forwards, with face raised toward heaven.” Erasmus Alber, the table companion, described Luther as well-proportioned and spoke of his general appearance in highest praise. …

One important aspect of his general appearance, noted by every observer, was Luther’s unusual eyes. Melanchthon made a casual remark that Luther’s eyes were brown and compared them to the eyes of a lion or falcon. Kessler, when he became Luther’s pupil, observed that his professor had “deep black eyes and brows, sparkling and burning like stars, so that one could hardly bear looking at them.” Erasmus Alber also likened them to falcon’s eyes. Melanchthon added the observation that the eyes were brown, with golden rings around the edges, as in the case of eagles or men of genius. Nikolaus Selnecker also compared Luther’s eyes to those of a hawk, falcon, fox, and eagle, having a fiery, burning sparkle. …

[Roman] Catholics, on the other hand, saw in these eyes diabolic powers. After the first meeting with Luther at Augsburg, [Cardinal] Cajetan would have no more to do with this man, the “beast with the deep-seated eyes,” because “strange ideas were flitting through his head.” Aleander wrote in his dispatches to the Pope that when Luther left his carriage at Worms, he looked over the crowd with “demoniac eyes.” Johannes Dantiscus, later a [Roman] Catholic bishop, visited Wittenberg in 1523 and noticed that Luther’s eyes were “unusually penetrating and unbelievably sparkling as one finds them now and then in those that are possessed.” His enemies also commonly compared him to a basilisk, that fabulous reptile which hypnotizes and slowly crawls upon its helpless prey. …

Another attribute which greatly enhanced Luther’s physical qualifications as a preacher and professor was his voice. It was clear, penetrating, and of pleasing timbre, which, added to its sonorous, baritone resonance, contributed much to his effectiveness as a public speaker. … Luther’s students enjoyed his classroom lectures because of the pleasing qualities of his delivery. Erasmus Alber added that he never shouted, yet his clear, ringing voice could easily be heard.

Sources

Cranach Digital Archive, combined with the power of Google

E. G. Schwiebert, Luther and His Times: The Reformation from a New Perspective (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1950), pp. 571-576

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: His Road to Reformation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1985), pp. 318,412

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: The Preservation of the Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), Plates between pp. 14 & 15, and p. 378