Luther’s Decline in Old Age

Left: Luther’s most infamous work, On the Jews and Their Lies (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1543). Right: Luther’s probably second-most infamous work, Against the Papacy in Rome, Instituted by the Devil (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1545). For more on the accompanying woodcut by Lucas Cranach, see #8 below.

Luther historians like Martin Brecht would have us “guard against too hastily explaining Luther’s actions in the last years of his life as the grumpiness of an old man.” But those who think this is too easy or simple an explanation have not fought the fight Luther had to fight or experienced his frustrations and disappointments. (Rf. Daniel Deutschlander’s brilliant treatment of the Christian’s struggles in the so-called golden years in The Theology of the Cross, pp. 187–93. Luther’s struggles were compounded many times over.) In a letter to Jakob Probst, bishop of Bremen, dated March 26, 1542, he wrote, “I am exhausted by age and work, ‘old, cold, and sorry to behold’ (as they say).” He closed by saying, “I have had enough of this life, or more accurately, of this extremely bitter death.”

Nevertheless, increasing cantankerousness in advancing age is an explanation, not an excuse. Two of his mounting frustrations in particular got the better of him in these years.

That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew (Wittenberg: Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1523).

Luther and the Jews

In 1523 Luther had written That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew. In addition to defending himself against false rumors in it, he also attempted to win the Jews of his day as converts to the Christian gospel. He suspected that the reason more Jews hadn’t converted to Christianity up to that point was because the only Christianity they had been able to convert to was that of the pope and his followers. “They have dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs and not humans; they have afforded them nothing more than to insult them and take their property. … I hope that, if we deal with the Jews in a friendly way and give them careful instruction from Holy Scripture, many of them will become true Christians and return to the faith of their fathers, the prophets and patriarchs.”

Luther then went on to demonstrate patiently and thoroughly that the Christian faith was indeed the faith of the Old Testament prophets and patriarchs. He thought it enough to convince the Jews that Jesus was the promised Messiah; the teaching of Jesus’ divinity could wait for the time being. “For they have been led astray so badly and for such a long time that we must proceed cautiously with them… If we want to help them, then we must not practice the pope’s law with them but the law of Christian love, receiving them cordially and permitting them to trade and work with us. That way they will acquire the occasion and opportunity to be with us and around us and to hear and witness our Christian teaching and living.” He even joked that the papists might now begin to denounce him as a Jew as a result of the book.

Judensau, sandstone relief on the exterior of the parish church chancel in Wittenberg, c. 1304 (© Red Brick Parsonage, 2013).

Indeed, this book is remarkable when placed in the context of Luther’s thoroughly anti-Semitic culture. To this day you can visit the parish church in Wittenberg and see an anti-Semitic sandstone relief on the southeast corner of the building, called the Judensau or Jewish Sow, which preceded Luther’s arrival in Wittenberg by more than 200 years. It depicts Jewish boys suckling from a sow—an unclean animal in the Jewish religion (rf. Leviticus 11:1–8)—and a Jewish rabbi looking into the sow’s rear end to read the Talmud. This characterizes the world in which Luther grew up, lived, and worked.

But Luther’s hopes for the conversion of many Jews—hopes he also expressed in a letter he wrote to his friend Bernhard, a baptized Jew, in May or June 1523—were not realized, and he grew increasingly frustrated with them on the whole. In part, his disappointments were fueled by reports and rumors about the Jews originating with Jewish converts to Christianity. After receiving and reading an unidentified treatise containing a dialogue between a Jew and a Christian in an attempt to convert Christians to Judaism, Luther penned On the Jews and Their Lies (pictured at the head) at the end of 1542. The first two sections were relatively tame, but the third section is now infamous. In view of the frightful rumors surrounding their activity and their supposedly negative effect on the economy, Luther advised the following (directly quoted from the book):

- to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn…

- that their houses also be razed and destroyed. … Instead they might be lodged under a roof or in a barn, like the gypsies.

- that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings…be taken from them.

- that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb.

- that safe-conduct on the highways be abolished completely for the Jews.

- that usury be prohibited to them, and that all cash and treasure of silver and gold be taken from them and put aside for safekeeping. … Whenever a Jew is sincerely converted, he should be handed one hundred, two hundred, or three hundred florins, as personal circumstances may suggest.

- putting a flail, an ax, a hoe, a spade, a distaff, or a spindle into the hands of young, strong Jews and Jewesses and letting them earn their bread in the sweat of their brow… But if we are afraid that they might harm us or our wives, children, servants, cattle, etc., if they had to serve and work for us…then let us emulate the common sense of other nations such as France, Spain, Bohemia, etc. [further proof of the anti-Semitic world in which Luther lived], compute with them how much their usury has extorted from us, divide this amicably, but then eject them forever from the country.

Martin Sasse, Regional Bishop of Thuringia, ed., Martin Luther on the Jews: Away with Them!, a 1938 pamphlet defending the events of the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht).

Not surprisingly, this work was later utilized by Hitler and the Nazis to try and attract Christians to their cause.

On the one hand, it is folly merely to equate Luther’s religious post-judice (frustration resulting from the Jews’ rejection of the gospel) with Hitler and the Nazi leaders’ racial prejudice (fundamental disdain for the Jewish ethnicity). On the other hand, especially if we are Lutheran, we must acknowledge two things:

- The deep contradiction in Luther’s own theology, not only when compared to what he condemned and advocated in his earlier and better 1523 work, but also when compared to his previous assertions about the distinction between Church and State and the roles of each. For example, in his Admonition to Peace (1525) he had written that “no ruler ought to prevent anyone from teaching or believing what he pleases, whether it is the gospel or lies. It is enough if he prevents the teaching of sedition and rebellion.” But in On the Jews and Their Lies Luther tries to defend and advance Christ’s kingdom using the power of worldly government, even though Christ himself said his kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36).

- Even supposing that it were biblical to enlist the power of the State in defending and advancing Christ’s kingdom, Luther’s advice in this work would still be unchristian and abominable. How could such treatment ever win hearts, which is what Christianity is always after?

Luther and the Pope

This series has already covered Luther’s biblical conviction of the papacy as the Antichrist. In February and March 1545 Luther gave full, unrestrained vent to his pent-up frustrations with the pope, who had already convoked the Council of Trent (rf. woodcut #3 below). The result was Against the Papacy in Rome, Instituted by the Devil (pictured at the head), printed at the end of March.

While he was working on this book, he also designed a series of ten depictions of the papacy—not in the sense of drawing them himself, but in the sense of describing what he wanted artist Lucas Cranach to produce for him. He also composed a short poem, consisting of two distichs, to accompany each one. Cranach then created the woodcuts according to Luther’s designs and had them published with a Latin title at the top and Luther’s poem at the bottom of each. Today this collection of woodcuts is called Abbildung des Papsttums, or Portrayal of the Papacy. They consist of the following, with Luther’s corresponding poem as the caption of each:

1. Birth and Origin of the Pope: A she-devil gives birth to the pope and cardinals. In the background on the right Megaera, one of the Furies in Greek mythology (the Furies executed the curses pronounced on criminals), serves as the baby pope’s wet-nurse. Alecto, another of the Furies, serves as his nursemaid, rocking him and feeding him honey. Tisiphone, the last of the Furies, teaches the toddler pope to walk. Luther himself criticized Cranach for depicting the pope’s birth so crudely, saying that he should have been more considerate of the female sex.

Hier wird geborn der Widerchrist

Megera sein Seugamme ist:

Alecto sein Kindermegdlin

Tisiphone die gengelt jn.

2. The Monster of Rome, Found Dead in the Tiber River in 1496: This was actually a reprint of a 1523 woodcut by Cranach. The births of freaks or “monsters” in Luther’s day were viewed as evil omens or signs (informative post on this here). So when Melanchthon found out about an alleged monster that had been found dead in the Tiber River in 1496 with head of a donkey, the body of a woman, the skin of a fish, different kinds of feet, and so on (see all the details in the woodcut), and shared it with Luther, Luther of course took it as a sign that God was telling people what the bishop of Rome had become. This depiction was commonly called der Papstesel, the pope-ass, which also unfortunately became the common way not a few German evangelicals referred to the pope.

Was Gott selbs von dem Bapstum helt

Zeigt dis schrecklich bild hie gestelt:

Dafür jederman grawen solt

Wenn ers zu hertzen nemen wolt.

3. The Pope Gives a Council in Germany: The council initially announced in 1536 (the announcement that prompted the Smalcald Articles of 1537) was finally convened by the pope in Trento—a city at the time in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation—in December 1545, the now infamous Council of Trent. However by that time Luther and his followers had given up all hope of a council correcting Roman doctrine and practice and restoring the relationship between the Roman Church and the Lutherans. Here the pope giving a council is depicted as him riding a sow with a handful of his own waste in his hand, which the sow sniffs at greedily and to which the pope gives his paternal blessing. Basically Luther is saying that the pope views Germany as a sow which he can ride as he wishes and to which he can feed his waste—namely whatever decisions the council would render—and the pope expects Germany to be happy with all of it.

Saw du must dich lassen reiten.

Und wol sporen zu beiden seiten.

Du wilt han ein Concilium

Ja dafür hab dir mein merdrum:

4. The Pope as Doctor of Theology and Master of the Faith: Luther’s own biting poem beneath this woodcut says it all: “The pope alone can interpret the Scriptures and sweep out error—just as much as the ass alone can play the pipes and understand the notes correctly.”

Der Bapst kan allein auslegen

Die schrifft: und jrthum ausfegen

Wie der Esel allein pfeiffen

Kan: und die noten recht greiffen.

5. The Pope Thanks the Emperors for the Immense Benefits He Has Received: Pope Clement IV is depicted as beheading Conradin of Hohenstaufen (1252-1268), King of Sicily and Naples. Clement doubtless did not perform the execution himself, but was responsible for it. Luther used this as a metaphor for the pope’s ingratitude for all the benefits that had been given to the papacy by the emperors over the years.

Gros gut die Kaiser han gethan

Dem Bapst: und ubel gelegt an.

Dafür jm der Bapst gedanckt hat

Wie dis bild dir die warheit sagt.

6. Here the Pope, Obedient to St. Peter, Pays Honor to the King: This woodcut, not pictured here, also was not included in some editions of the collection. It shows the pope placing his foot on the neck of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and so the title is clearly sarcastic. The apostle Peter says to submit to kings and honor them (1 Peter 2:13, 17), but the pope, who is the supposed successor of St. Peter, does the opposite. Luther’s accompanying poem reads: “Here the pope openly shows by his deeds that he is the enemy of God and men. What God creates and wants to have honored, the most holy man tramples with his feet.”

7. The Just Rewards of the Most Satanic Pope and His Cardinals: In his poem, Luther said that if the pope and cardinals were to receive what they deserved in the form of earthly punishment (and not just the eternal punishment they can anticipate), this is what it would look like. The pope (on the far right) and three cardinals hang from a gallows. Because of their blasphemies against God and his word, their tongues are nailed to the gallows next to their heads (the hangman is in the process of nailing the pope’s tongue to the crosspiece). Demons receive their souls and carry them away.

Wenn zeitlich gestrafft solt werden:

Bapst und Cardinel auff erden,

Jr lesterzung verdienet het:

Wie jr recht hie gemalet steht.

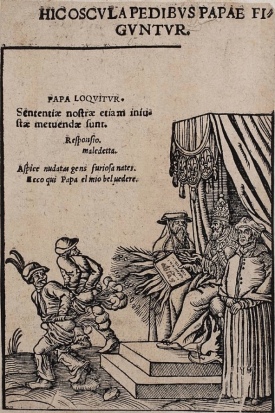

8. The Kingdom of Satan and the Pope (2 Thessalonians 2): This is by far the most famous of the woodcuts, since it was also used for the title page of Against the Papacy in Rome, Instituted by the Devil. The pope, with long donkey ears, sits enthroned in the jaws of hell and is waited on by various demons.

Jn aller Teufel namen sitzt

Alhie der Bapst: offenbart jtzt:

Das er sey der recht Widerchrist

So in der schrift verkündigt ist:

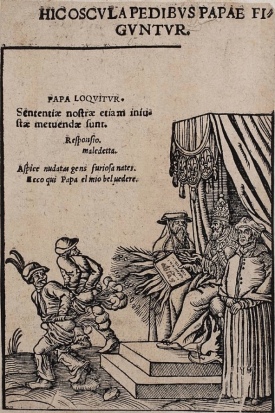

9. Here the Kissing of the Pope’s Feet Is Taunted: The pope is holding his ban or excommunication, which is emanating rays. In order to avoid having the ban fall upon them, these two peasants have been summoned to kiss the pope’s feet in repentance. Instead they curse his ban (“Maledetta” is Italian for “damned or accursed thing”), turn around to leave, moon him (in his poem, Luther calls this showing the pope the “Bel vedere,” Italian for “beautiful sight”), and pass gas at him as they go.

Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim bann

Und sey nicht so zorniger man.

Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre

Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere.

10. The Pope Is Worshipped As an Earthly God: On a podium (altar?) decorated with the papal keys (which, however, are mere skeleton keys, showing that they have no power, because the pope does not use them according to Christ’s institution) sits an inverted papal tiara or crown. A peasant is defecating into it, while another one gets ready to do so. Luther’s poem for this woodcut reads: “The pope has done to Christ’s kingdom as they are treating his crown here. ‘Pay her back double,’ says the Spirit [in Revelation 18:6]. ‘Go ahead and fill it up’ [a play on his own translation of Rev 18:7]—it is God who says so.” To paraphrase: After all the “crap” the pope, as fallen Babylon, has given you true Christians, put twice as much crap in his crown for him to wear.

Bapst hat dem reich Christi gethon

Wie man hie handelt seine Cron. (Apo. 18)

Machts jr zweifeltig. spricht der geist

Schenkt getrost ein: Got ists ders heist

It will come as no surprise that, as went the woodcuts, so went the book. Luther speaks the truth, but he does so in such incredibly crude and indefensible ways that he must fall under the apostle Paul’s judgment of being “only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal” (1 Corinthians 13:1). Here is a characteristic excerpt:

This, this, this is how one should lie and blaspheme if he wants to be a real pope. Dear God, what a completely and exceedingly brazen and blasphemous lying yapper the pope is. He speaks just as though there were no one on earth who knew that the four chief councils, and many others besides, were held without the Roman Church. Instead he thinks this way: “Since I am an uncivilized ass and do not read books, then there must not be anyone in the world who reads them. But when I sound out my assy braying—Hee-aw! Hee-aw! [German: Chika, Chika]—or if I just let out an ass fart, then they had better regard it all as an article of faith. If not, then Saints Peter and Paul, yes, God himself will be angry with them.” For God is not God anymore; there is only the Ass-God in Rome, where the great, uncivilized asses (the pope and the cardinals) ride on asses that are better than they.

It should go without saying that no Lutheran wears that badge because he worships Luther or thinks he was inspired by the Holy Spirit or without sin. Lutherans wear that badge because of Luther’s Christo-centric theology with its emphasis on grace, faith in Christ, and the authority of Holy Scripture.

Sources

Dr. Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette, ed., Dr. Martin Luthers Briefe, Sendschreiben und Bedenken, fünfter Theil (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1828), pp. 450–52 (no. 2056)

Woodcuts and distichs from Abbildung des Papsttums in Ein Buch allerlei Rüstung von der Hand darein zu schreiben geistlich und weltlich, pp. 42–59

Helmar Junghans, Wittenberg als Lutherstadt, 2nd ed. (Union Verlag Berlin, 1982), picture #10

Helmut T. Lehmann and Eric W. Gritsch, eds., Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966), 41:257ff

Helmut T. Lehmann and Walther I. Brandt, eds., Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1962), 45:195ff

Helmut T. Lehmann and Robert C. Schultz, eds., Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1967), 46:22

Helmut T. Lehmann and Franklin Sherman, eds., Luther’s Works, trans. Martin H. Bertram (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971), 47:121ff, esp. pp. 137, 268ff

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: Shaping and Defining the Reformation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1990), pp. 112–13

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: The Preservation of the Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), pp. 229–35, 333–51, 357–67

Martin Luther, Das Jhesus Christus eyn geborner Jude sey (Wittenberg: Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1523)

Martin Luther, Wider das Bapstum zu Rom vom Teuffel gestifft (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1545)

St. Louis Edition of Luther’s Works 20:1822–5