Luther Visualized 19 – In Decline

November 28, 2017 Leave a comment

Luther’s Decline in Old Age

Left: Luther’s most infamous work, On the Jews and Their Lies (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1543). Right: Luther’s probably second-most infamous work, Against the Papacy in Rome, Instituted by the Devil (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1545). For more on the accompanying woodcut by Lucas Cranach, see #8 below.

Luther historians like Martin Brecht would have us “guard against too hastily explaining Luther’s actions in the last years of his life as the grumpiness of an old man.” But those who think this is too easy or simple an explanation have not fought the fight Luther had to fight or experienced his frustrations and disappointments. (Rf. Daniel Deutschlander’s brilliant treatment of the Christian’s struggles in the so-called golden years in The Theology of the Cross, pp. 187–93. Luther’s struggles were compounded many times over.) In a letter to Jakob Probst, bishop of Bremen, dated March 26, 1542, he wrote, “I am exhausted by age and work, ‘old, cold, and sorry to behold’ (as they say).” He closed by saying, “I have had enough of this life, or more accurately, of this extremely bitter death.”

Nevertheless, increasing cantankerousness in advancing age is an explanation, not an excuse. Two of his mounting frustrations in particular got the better of him in these years.

Luther and the Jews

In 1523 Luther had written That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew. In addition to defending himself against false rumors in it, he also attempted to win the Jews of his day as converts to the Christian gospel. He suspected that the reason more Jews hadn’t converted to Christianity up to that point was because the only Christianity they had been able to convert to was that of the pope and his followers. “They have dealt with the Jews as if they were dogs and not humans; they have afforded them nothing more than to insult them and take their property. … I hope that, if we deal with the Jews in a friendly way and give them careful instruction from Holy Scripture, many of them will become true Christians and return to the faith of their fathers, the prophets and patriarchs.”

Luther then went on to demonstrate patiently and thoroughly that the Christian faith was indeed the faith of the Old Testament prophets and patriarchs. He thought it enough to convince the Jews that Jesus was the promised Messiah; the teaching of Jesus’ divinity could wait for the time being. “For they have been led astray so badly and for such a long time that we must proceed cautiously with them… If we want to help them, then we must not practice the pope’s law with them but the law of Christian love, receiving them cordially and permitting them to trade and work with us. That way they will acquire the occasion and opportunity to be with us and around us and to hear and witness our Christian teaching and living.” He even joked that the papists might now begin to denounce him as a Jew as a result of the book.

Judensau, sandstone relief on the exterior of the parish church chancel in Wittenberg, c. 1304 (© Red Brick Parsonage, 2013).

Indeed, this book is remarkable when placed in the context of Luther’s thoroughly anti-Semitic culture. To this day you can visit the parish church in Wittenberg and see an anti-Semitic sandstone relief on the southeast corner of the building, called the Judensau or Jewish Sow, which preceded Luther’s arrival in Wittenberg by more than 200 years. It depicts Jewish boys suckling from a sow—an unclean animal in the Jewish religion (rf. Leviticus 11:1–8)—and a Jewish rabbi looking into the sow’s rear end to read the Talmud. This characterizes the world in which Luther grew up, lived, and worked.

But Luther’s hopes for the conversion of many Jews—hopes he also expressed in a letter he wrote to his friend Bernhard, a baptized Jew, in May or June 1523—were not realized, and he grew increasingly frustrated with them on the whole. In part, his disappointments were fueled by reports and rumors about the Jews originating with Jewish converts to Christianity. After receiving and reading an unidentified treatise containing a dialogue between a Jew and a Christian in an attempt to convert Christians to Judaism, Luther penned On the Jews and Their Lies (pictured at the head) at the end of 1542. The first two sections were relatively tame, but the third section is now infamous. In view of the frightful rumors surrounding their activity and their supposedly negative effect on the economy, Luther advised the following (directly quoted from the book):

- to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn…

- that their houses also be razed and destroyed. … Instead they might be lodged under a roof or in a barn, like the gypsies.

- that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings…be taken from them.

- that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb.

- that safe-conduct on the highways be abolished completely for the Jews.

- that usury be prohibited to them, and that all cash and treasure of silver and gold be taken from them and put aside for safekeeping. … Whenever a Jew is sincerely converted, he should be handed one hundred, two hundred, or three hundred florins, as personal circumstances may suggest.

- putting a flail, an ax, a hoe, a spade, a distaff, or a spindle into the hands of young, strong Jews and Jewesses and letting them earn their bread in the sweat of their brow… But if we are afraid that they might harm us or our wives, children, servants, cattle, etc., if they had to serve and work for us…then let us emulate the common sense of other nations such as France, Spain, Bohemia, etc. [further proof of the anti-Semitic world in which Luther lived], compute with them how much their usury has extorted from us, divide this amicably, but then eject them forever from the country.

Martin Sasse, Regional Bishop of Thuringia, ed., Martin Luther on the Jews: Away with Them!, a 1938 pamphlet defending the events of the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht).

Not surprisingly, this work was later utilized by Hitler and the Nazis to try and attract Christians to their cause.

On the one hand, it is folly merely to equate Luther’s religious post-judice (frustration resulting from the Jews’ rejection of the gospel) with Hitler and the Nazi leaders’ racial prejudice (fundamental disdain for the Jewish ethnicity). On the other hand, especially if we are Lutheran, we must acknowledge two things:

- The deep contradiction in Luther’s own theology, not only when compared to what he condemned and advocated in his earlier and better 1523 work, but also when compared to his previous assertions about the distinction between Church and State and the roles of each. For example, in his Admonition to Peace (1525) he had written that “no ruler ought to prevent anyone from teaching or believing what he pleases, whether it is the gospel or lies. It is enough if he prevents the teaching of sedition and rebellion.” But in On the Jews and Their Lies Luther tries to defend and advance Christ’s kingdom using the power of worldly government, even though Christ himself said his kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36).

- Even supposing that it were biblical to enlist the power of the State in defending and advancing Christ’s kingdom, Luther’s advice in this work would still be unchristian and abominable. How could such treatment ever win hearts, which is what Christianity is always after?

Luther and the Pope

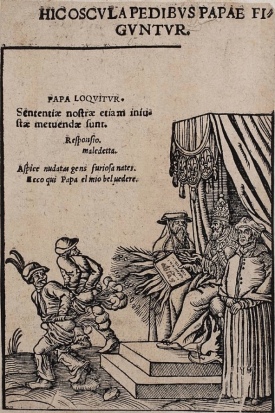

This series has already covered Luther’s biblical conviction of the papacy as the Antichrist. In February and March 1545 Luther gave full, unrestrained vent to his pent-up frustrations with the pope, who had already convoked the Council of Trent (rf. woodcut #3 below). The result was Against the Papacy in Rome, Instituted by the Devil (pictured at the head), printed at the end of March.

While he was working on this book, he also designed a series of ten depictions of the papacy—not in the sense of drawing them himself, but in the sense of describing what he wanted artist Lucas Cranach to produce for him. He also composed a short poem, consisting of two distichs, to accompany each one. Cranach then created the woodcuts according to Luther’s designs and had them published with a Latin title at the top and Luther’s poem at the bottom of each. Today this collection of woodcuts is called Abbildung des Papsttums, or Portrayal of the Papacy. They consist of the following, with Luther’s corresponding poem as the caption of each:

1. Birth and Origin of the Pope: A she-devil gives birth to the pope and cardinals. In the background on the right Megaera, one of the Furies in Greek mythology (the Furies executed the curses pronounced on criminals), serves as the baby pope’s wet-nurse. Alecto, another of the Furies, serves as his nursemaid, rocking him and feeding him honey. Tisiphone, the last of the Furies, teaches the toddler pope to walk. Luther himself criticized Cranach for depicting the pope’s birth so crudely, saying that he should have been more considerate of the female sex.

Hier wird geborn der Widerchrist

Megera sein Seugamme ist:

Alecto sein Kindermegdlin

Tisiphone die gengelt jn.

2. The Monster of Rome, Found Dead in the Tiber River in 1496: This was actually a reprint of a 1523 woodcut by Cranach. The births of freaks or “monsters” in Luther’s day were viewed as evil omens or signs (informative post on this here). So when Melanchthon found out about an alleged monster that had been found dead in the Tiber River in 1496 with head of a donkey, the body of a woman, the skin of a fish, different kinds of feet, and so on (see all the details in the woodcut), and shared it with Luther, Luther of course took it as a sign that God was telling people what the bishop of Rome had become. This depiction was commonly called der Papstesel, the pope-ass, which also unfortunately became the common way not a few German evangelicals referred to the pope.

Was Gott selbs von dem Bapstum helt

Zeigt dis schrecklich bild hie gestelt:

Dafür jederman grawen solt

Wenn ers zu hertzen nemen wolt.

3. The Pope Gives a Council in Germany: The council initially announced in 1536 (the announcement that prompted the Smalcald Articles of 1537) was finally convened by the pope in Trento—a city at the time in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation—in December 1545, the now infamous Council of Trent. However by that time Luther and his followers had given up all hope of a council correcting Roman doctrine and practice and restoring the relationship between the Roman Church and the Lutherans. Here the pope giving a council is depicted as him riding a sow with a handful of his own waste in his hand, which the sow sniffs at greedily and to which the pope gives his paternal blessing. Basically Luther is saying that the pope views Germany as a sow which he can ride as he wishes and to which he can feed his waste—namely whatever decisions the council would render—and the pope expects Germany to be happy with all of it.

Saw du must dich lassen reiten.

Und wol sporen zu beiden seiten.

Du wilt han ein Concilium

Ja dafür hab dir mein merdrum:

4. The Pope as Doctor of Theology and Master of the Faith: Luther’s own biting poem beneath this woodcut says it all: “The pope alone can interpret the Scriptures and sweep out error—just as much as the ass alone can play the pipes and understand the notes correctly.”

Der Bapst kan allein auslegen

Die schrifft: und jrthum ausfegen

Wie der Esel allein pfeiffen

Kan: und die noten recht greiffen.

5. The Pope Thanks the Emperors for the Immense Benefits He Has Received: Pope Clement IV is depicted as beheading Conradin of Hohenstaufen (1252-1268), King of Sicily and Naples. Clement doubtless did not perform the execution himself, but was responsible for it. Luther used this as a metaphor for the pope’s ingratitude for all the benefits that had been given to the papacy by the emperors over the years.

Gros gut die Kaiser han gethan

Dem Bapst: und ubel gelegt an.

Dafür jm der Bapst gedanckt hat

Wie dis bild dir die warheit sagt.

6. Here the Pope, Obedient to St. Peter, Pays Honor to the King: This woodcut, not pictured here, also was not included in some editions of the collection. It shows the pope placing his foot on the neck of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, and so the title is clearly sarcastic. The apostle Peter says to submit to kings and honor them (1 Peter 2:13, 17), but the pope, who is the supposed successor of St. Peter, does the opposite. Luther’s accompanying poem reads: “Here the pope openly shows by his deeds that he is the enemy of God and men. What God creates and wants to have honored, the most holy man tramples with his feet.”

7. The Just Rewards of the Most Satanic Pope and His Cardinals: In his poem, Luther said that if the pope and cardinals were to receive what they deserved in the form of earthly punishment (and not just the eternal punishment they can anticipate), this is what it would look like. The pope (on the far right) and three cardinals hang from a gallows. Because of their blasphemies against God and his word, their tongues are nailed to the gallows next to their heads (the hangman is in the process of nailing the pope’s tongue to the crosspiece). Demons receive their souls and carry them away.

Wenn zeitlich gestrafft solt werden:

Bapst und Cardinel auff erden,

Jr lesterzung verdienet het:

Wie jr recht hie gemalet steht.

8. The Kingdom of Satan and the Pope (2 Thessalonians 2): This is by far the most famous of the woodcuts, since it was also used for the title page of Against the Papacy in Rome, Instituted by the Devil. The pope, with long donkey ears, sits enthroned in the jaws of hell and is waited on by various demons.

Jn aller Teufel namen sitzt

Alhie der Bapst: offenbart jtzt:

Das er sey der recht Widerchrist

So in der schrift verkündigt ist:

9. Here the Kissing of the Pope’s Feet Is Taunted: The pope is holding his ban or excommunication, which is emanating rays. In order to avoid having the ban fall upon them, these two peasants have been summoned to kiss the pope’s feet in repentance. Instead they curse his ban (“Maledetta” is Italian for “damned or accursed thing”), turn around to leave, moon him (in his poem, Luther calls this showing the pope the “Bel vedere,” Italian for “beautiful sight”), and pass gas at him as they go.

Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim bann

Und sey nicht so zorniger man.

Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre

Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere.

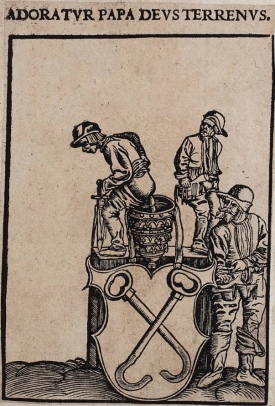

10. The Pope Is Worshipped As an Earthly God: On a podium (altar?) decorated with the papal keys (which, however, are mere skeleton keys, showing that they have no power, because the pope does not use them according to Christ’s institution) sits an inverted papal tiara or crown. A peasant is defecating into it, while another one gets ready to do so. Luther’s poem for this woodcut reads: “The pope has done to Christ’s kingdom as they are treating his crown here. ‘Pay her back double,’ says the Spirit [in Revelation 18:6]. ‘Go ahead and fill it up’ [a play on his own translation of Rev 18:7]—it is God who says so.” To paraphrase: After all the “crap” the pope, as fallen Babylon, has given you true Christians, put twice as much crap in his crown for him to wear.

Bapst hat dem reich Christi gethon

Wie man hie handelt seine Cron. (Apo. 18)

Machts jr zweifeltig. spricht der geist

Schenkt getrost ein: Got ists ders heist

It will come as no surprise that, as went the woodcuts, so went the book. Luther speaks the truth, but he does so in such incredibly crude and indefensible ways that he must fall under the apostle Paul’s judgment of being “only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal” (1 Corinthians 13:1). Here is a characteristic excerpt:

This, this, this is how one should lie and blaspheme if he wants to be a real pope. Dear God, what a completely and exceedingly brazen and blasphemous lying yapper the pope is. He speaks just as though there were no one on earth who knew that the four chief councils, and many others besides, were held without the Roman Church. Instead he thinks this way: “Since I am an uncivilized ass and do not read books, then there must not be anyone in the world who reads them. But when I sound out my assy braying—Hee-aw! Hee-aw! [German: Chika, Chika]—or if I just let out an ass fart, then they had better regard it all as an article of faith. If not, then Saints Peter and Paul, yes, God himself will be angry with them.” For God is not God anymore; there is only the Ass-God in Rome, where the great, uncivilized asses (the pope and the cardinals) ride on asses that are better than they.

It should go without saying that no Lutheran wears that badge because he worships Luther or thinks he was inspired by the Holy Spirit or without sin. Lutherans wear that badge because of Luther’s Christo-centric theology with its emphasis on grace, faith in Christ, and the authority of Holy Scripture.

Sources

Dr. Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette, ed., Dr. Martin Luthers Briefe, Sendschreiben und Bedenken, fünfter Theil (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1828), pp. 450–52 (no. 2056)

Woodcuts and distichs from Abbildung des Papsttums in Ein Buch allerlei Rüstung von der Hand darein zu schreiben geistlich und weltlich, pp. 42–59

Helmar Junghans, Wittenberg als Lutherstadt, 2nd ed. (Union Verlag Berlin, 1982), picture #10

Helmut T. Lehmann and Eric W. Gritsch, eds., Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1966), 41:257ff

Helmut T. Lehmann and Walther I. Brandt, eds., Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1962), 45:195ff

Helmut T. Lehmann and Robert C. Schultz, eds., Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1967), 46:22

Helmut T. Lehmann and Franklin Sherman, eds., Luther’s Works, trans. Martin H. Bertram (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971), 47:121ff, esp. pp. 137, 268ff

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: Shaping and Defining the Reformation (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1990), pp. 112–13

Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: The Preservation of the Church (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), pp. 229–35, 333–51, 357–67

Martin Luther, Das Jhesus Christus eyn geborner Jude sey (Wittenberg: Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1523)

Martin Luther, Wider das Bapstum zu Rom vom Teuffel gestifft (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1545)

Finishing the Race

December 2, 2015 Leave a comment

A Commentary on 2 Timothy 4:6–8

By Johann Gerhard, Th. D.

Translator’s Preface

The following was translated from Adnotationes ad Posteriorem D. Pauli ad Timotheum Epistolam, in Quibus Textus Declaratur, Quaestiones Dubiae Solvuntur, Observationes Eruuntur, & Loca in Speciem Pugnantia quam Brevissime Conciliantur (Commentary on St. Paul’s Second Letter to Timothy, in Which the Text Is Explained, Difficult Questions Are Answered, Observations Are Drawn Out, and Seemingly Contradictory Passages Are Reconciled as Concisely as Possible) by Johann Gerhard, Th.D. (Jena: Steinmann, 1643), 78–86; available from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. I also consulted the 1666 Jena edition, pp. 205–13.

This translation was prepared in connection with an exegetical presentation assigned to me for a circuit meeting in Merrill, Wisconsin, on December 7, 2015.

The footnotes are mine, and are for the most part an attempt to cite Gerhard’s sources more exactly. “PG” and “PL” stand for J.-P. Migne’s collections of the writings of the church fathers, Patrologia Graeca and Patrologia Latina respectively.

May the Holy Spirit use the apostle Paul’s words to inspire us to contend honorably and well in the good contest in which God has graciously placed us, so that we finish our race as Paul did, satisfied with our earthly lot and confident of the crown of righteousness that awaits us.

2 Timothy 4:6–8

Paraphrase: I am being offered and poured out in the manner of a sacrifice.

This kind of metaphor is taken from the sacrifices of the Old Testament, to which drink offerings used to be added.

At the same time he is alluding to the punishment that he is going to undergo and its fruit, the verification of the truth of the gospel. For he says that he is being poured out [libari], that is, that he is about to be poured out [libatum iri], that is, that his blood is about to be shed in order to ratify the truth of the doctrine of the gospel, just as agreements were ratified with drink offerings [libaminibus], that is, with the pouring out of wine which the contracting parties had first sampled [libaverant], that is, tasted with the edge of their lips.

Certainly our death is a sacrifice that we offer to God, but that sacrifice ought to be a willing one. Therefore when the hour of death comes, let us follow after our Lord, not with reluctance and groaning, but with a ready spirit.

A passage parallel to this one is found in Philippians 2:17: ἀλλ᾽ εἰ καὶ σπένδομαι ἐπὶ τῇ θυσίᾳ καὶ λειτουργίᾳ τῆς πίστεως ὑμῶν, χαίρω [But even if I am being poured out on the sacrifice and service of your faith, I rejoice].

The little word ἤδη [already] means that it will not be long before he is carried off to punishment and he ratifies the truth of the gospel with the pouring out of his blood.

“The time of my release [resolutionis],” namely from bodily fetters. Cyprian seems to have read ὁ καιρὸς ἐμῆς ἀναλήψεως [the time of my ascension].1 Some teach that Paul called it “release” [resolutionem] because through death the body is released (or dissolved) [resolvatur] into ashes, but the better reason was just given, namely that through death the fetter is loosened [solvatur] by which the soul was drawn together with the body.2

A parallel passage is Philippians 1:23: ἐπιθυμίαν ἔχων εἰς τὸ ἀναλῦσαι καὶ σὺν Χριστῷ εἶναι [having a desire for release and being with Christ].

Most interpreters conclude from this passage that out of all the Pauline epistles, this was the last one the apostle wrote, since the death he would suffer was already imminent. Rf. Eusebius’s Church History, Book 2, Chapter 22.3 Estius opposes this judgment in his section on the “Theme of the Epistle.”4 He is of the opinion that “this epistle is either the first or second of those that were produced in Rome, and was written many years before Paul’s death, namely in Nero’s third or fourth year, since Paul’s martyrdom occured during Nero’s thirteenth year.”5 He proves his opinion with the following arguments:

In his exposition of verse 13 in this chapter, he strengthens his opinion with another argument: If [Paul] was thinking that the day of his death was already impending as he wrote this epistle, then what would be the point of his asking for the traveling clothes, or the box, or the scrolls that he had left in Troas some ten years ago, when they would not be of any further use to him?7

At the present passage he responds to the mainstream interpretation by saying that the apostle does not think “that he is already about to be carried off to martyrdom,” but that he is simply indicating that, “even though he is uncertain as to the time of his death or suffering, he is gradually being prepared for sacrifice through imprisonments and tribunals.”8 But this exposition does not capture the emphasis of the apostle’s words, and the strength of the arguments produced by Baronius and Estius is weak.

This is a flowery and sort of triumphant συμπλοκή [combination] linked together by asyndeton, in which he describes the course of his life using three distinct metaphors.

The first one is borrowed from a strong athlete: Τὸν ἀγῶνα τὸν καλὸν ἡγώνισμαι, certamen bonum certavi, “I have contended in the good” – that is, the noble, distinguished, and excellent – “contest.” Some want this to be understood as a running contest here, since it is immediately followed by cursum consummavi, “I have finished the race.” But it is more correct to say that the metaphor is taken particularly from a wrestling contest, which metaphor is also used in 1 Corinthians 9:25.

The second metaphor is borrowed from a strenuous runner: τὸν δρόμον τετέλεκα. He compares himself to those who run in a racecourse, which metaphor is used in the same way as the first, and he links it together with the first one taken from an athlete. See 1 Corinthians 9:24,26. Some want this metaphor to be taken from a journey, but the first explanation fits the context better.

The third metaphor is borrowed from an honorable soldier: τὴν πίστιν τετήρηκα. By the faith he not only understands the confident apprehending of Christ’s merit, but also the faith of duty or the faithfulness with respect to duty that he owed and promised to God. For he compares himself to a soldier who has pledged loyalty [fidem] to the emperor or to the general and keeps it faithfully. “This is what is sought in stewards, that a man be found faithful” (1 Corinthians 4:2).

Therefore Paul’s life has constituted the following:

“He says that he has [contended in the contest,] has finished [the] race[, has kept the faith], even though . . . the last act of his suffering and death still remained, because . . . he was already approaching the end of the contest and had firm confidence in the Lord regarding the part of the racecourse he still had to cover.”9 Cf. Augustine, A Treatise on the Merits and Forgiveness of Sins, Book 2, Chapter 16.10

Ambrose renders the Greek λοιπόν as quod reliquum est, “as for what remains.”11

He continues in the metaphor and calls the reward of the contest, race, and military service that have been completed commendably a crown, since it was customary for a crown to be given to those running in a racecourse and to soldiers.

But the happiness and glory of eternal life is called the crown of righteousness, not Paul’s righteousness, but God’s. And indeed the righteousness of God is understood not as that which judges according to the merits of works, but as that according to which God is steadfast in promises, and which does not pay a debt that has been earned, but a debt that has been freely promised.

Therefore it is the crown of righteousness because:

Estius asks how it can be called the crown of righteousness, since it is the crown of compassion (Psalm 103:4). He responds:

And later:

We respond:

As for the rest, the apostle says that that crown of righteousness has been “set aside for [him],” no doubt by God, by whom Paul was most confidently expecting to have it bestowed [reddendam] upon him. “I am certain that he is able to guard my deposit” (2 Timothy 1:12). That is why he immediately adds:

Estius emphasizes that Paul does not say, “will give [dabit],” but “will give back [reddet],” “just like some debt, or a loan or deposit, which needs to be paid back by law,” and he cites Theophylact and Oecumenius.18

We respond:

By ὁ Κύριος [the Lord] he understands Christ, whom he calls ὁ δίκαιος κριτής [the righteous judge], the one to whom the Father has given all judgment (John 5:22). The apostle notably says about this righteous judge that he is going to give the crown both to him (Paul) and to all who love his (the judge’s) appearing, from which it is clearly proved that the authority κριτικήν [to judge] is given to Christ as man.20

But Estius follows this up by saying that Christ is not going to present the elect with heavenly blessedness in any other way than by simply awarding the apostle Paul and the rest of the elect the crown that is owed to them through a judicial decision, since “to bless a creature effectively and properly belongs to uncreated authority alone.”21

We respond: But indeed that uncreated and infinite authority to bless a creature has been given to Christ the man through and on account of the personal union of the two natures in time. He will therefore not only pronounce a judicial decision with his external and audible voice, but he will also demonstrate his omniscience by exposing even the most hidden things of all people (1 Corinthians 4:5), and he will demonstrate his omnipotence with that which precedes the judgment—the resuscitation of the dead, the summoning and assembling of all people at the tribunal of judgment, and the effectual execution of the judicial sentencing. Power and glory that are truly divine are required in order to do all or any of these things, which is why Scripture says throughout that Christ is coming to judge in truly divine glory, power, and authority.

By ἐκείνῃ τῇ ἡμέρᾳ [that day] he understands the day of judgment, which is elsewhere called “the day of the Lord.”

Ἐναντιοφανές [Apparent Contradiction]: As far as his soul is concerned, Paul received that crown of righteousness immediately after his death. Why then does he say that Christ is not going to give it to him until the day of judgment?

We respond: He is talking about the fullest and most perfect blessedness, which will be bestowed not upon the soul, but upon the human consisting of soul and body.

From this passage it is concluded that the apostle was sure of his salvation. But Estius follows this up by saying that “Paul is not simply affirming here what is going to happen. Rather, he is either speaking optimistically [sermonem esse bonae fiduciae], as if to say, ‘I am certainly expecting and hoping to receive this crown from the Lord,’ or more likely, there is an implied condition, ‘The Lord will do this for me if I perserve all the way to my death.’”22 For Estius says that what Paul wrote in the letter to the Philippians “after this one to Timothy”23 stands against any certainty of salvation, “when he speaks as one who is still by no means completely certain: ‘if somehow I may attain to the resurrection which is from the dead’ (3:11).”24

We respond:

He is called the δίκαιος κριτής [righteous judge] because he will judge ἐν δικαιοσύνῃ [in righteousness] (Acts 17:31) and will execute that δικαίαν τοῦ θεοῦ κρίσιν [righteous judgment of God] which Paul describes this way in 2 Thessalonians 1:6,7: “It is just in God’s sight to repay tribulation to those who are troubling you, and to you who are undergoing tribulation to repay rest, along with us, when the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven . . .”

Those “who love [Christ’s] coming” are those who are waiting for him as their Savior with longing and vigilance, who daily prepare themselves for Christ’s coming, and who demonstrate that they love him and are eagerly waiting for his coming by earnestly devoting themselves to piety.

Estius suspects that the “familiar distributive” πᾶσι in the Greek text was a later addition, because:

We respond:

Endnotes

1 Gerhard may be referring to De Laude Martyrii (On the Glory of Martyrdom) 18 (PL 4, col. 828). This work is attributed to Cyprian with reservation.

2 Cf. Guilielmus Estius, In Omnes Beati Pauli et Aliorum Apostolorum Epistolas Commentaria (Paris, 1623), 852.2–853.1: “[Paul] calls death his ‘release’ [resolutionem] either because through death the body is released (or dissolved) [resolvatur] into ashes or, more likely, because through it the fetter is loosened [solvatur] with which the soul was drawn together with the body.” Cosmas Magalianus, Operis Hierarchici, sive, De Ecclesiastico Principatu, Liber II. in quo Beati Pauli Apostoli secunda ad Timotheum Ephesi Episcopum, & Primatem, Epistola, Commentariis illustratur (Lyon, France: Sumptibus Horatii Cardon, 1609), 180: “For death is the loosening [solutio] of the soul from the body, a departure, as it were, from the penitentiary in which it was being detained.”

3 PG 20, cols. 193–96. Rf. also Magalianus, op. cit., p. 8, where he not only cites Eusebius as such an interpreter, but also Chrysostom in his homilies on this epistle (rf. e.g. PG 62, col. 601) and Jerome in his Lives of Illustrious Men (rf. PL 23, col. 615–18).

4 Estius’s opposition is really based on the arguments of Cardinal Caesar Baronius, in tome 1 of his Annales Ecclesiastici. (Cardinal Baronius undertook his Annales in answer to the Lutheran church history compiled mainly by Matthias Flacius, the so-called Magdeburg Centuries.) Magalianus (op. cit., p. 9) also cites Alfonso Salmerón the Jesuit, in Salmerón’s first discussion (Prima Disputatio) on 2 Timothy (Disputationum in Epistolas Divi Pauli Tomus Tertius), in addition to Baronius, as going against the judgment of mainstream interpreters.

5 Estius, op. cit., p. 825.

6 Ibid., pp. 825–26. Estius does not actually include this argument in the “Theme of the Epistle,” as implied here, but in his comments on vs. 6 (p. 852.2), where he says that he will prove his assertion in his comments on Philemon 22.

7 Ibid., p. 856.1.

8 Ibid., p. 852.2.

9 Ibid., p. 853.1. In the original, it appears that Gerhard is citing Augustine (rf. next footnote), but he is actually citing Estius, who supports his interpretation by citing Augustine.

10 PL 44, cols. 165–66. In English editions, the citation in question appears in Chapter 24. The “Cf.” does not appear in Gerhard’s original (rf. preceding footnote).

11 On the Duties of the Clergy, Book 1, Chapter 15 (PL 16, col. 40). The Latin phrase, like the English, is somewhat ambiguous, referring either to remaining subject matter or to what remains in the future. In Schaff’s Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (vol. 10, p. 11) the phrase is rendered henceforth.

12 This reference does not seem to fit.

13 Estius, op. cit., p. 853.2.

14 Ibid., p. 854.1.

15 Latin: suo loco. This phrase occurs again later; both times it seems to be a reference to Gerhard’s well-known dogmatic treatise and magnum opus, Loci Theologici (Theological Topics).

16 Perhaps Gerhard meant to cite 40:13 (which corresponds to Romans 11:34). The actual Old Testament parallel to Romans 11:35 is Job 41:11.

17 PL 37, cols. 1445,1446. This corresponds to Psalm 110 in English Bibles.

18 Estius, op. cit., p. 853.2. Cf. Oecumenius in PG 119, cols. 233,234; Theophylact in PG 125, cols. 131,132.

19 “‘Lord my God, if I have done this, if there is injustice in my hands, if I have paid back [ἀνταπέδωκα] evil to those who pay me back [τοῖς ἀνταποδιδοῦσί μοι], may I then fall down empty at the hands of my enemies. May the enemy then hunt down my life and overtake it’ [Psalm 7:4–6a LXX]. It is customary for Scripture to apply the term ἀνταπόδοσις [repayment] not only to the usual circumstances, as repayment of something good or bad that already exists, but also to actions taking place first, as in the passage, ‘Pay back [Ἀνταπόδος] to your slave’ [Ps 118:17 LXX]. For instead of saying, ‘Give [Δὸς],’ ‘Pay back [Ἀνταπόδος]’ was said. Δόσις [giving], then, is the beginning of doing good; ἀπόδοσις [giving back] is the reciprocal measuring out of something equal for the good that one has experienced; ἀνταπόδοσις [paying back] is a sort of second beginning and going around [περίοδος] of the good and bad things being paid to certain people. But I think that, whenever the discourse is seeking repayment [τὴν ἀνταπόδοσιν], making, as it were, a sort of formal demand instead of a request, it yields something like the following sense: ‘Show me the same obligation of care that progenitors automatically owe their offspring by nature’” (PG 29, col. 233; translation mine).

20 “appearing” in this sentence is adventum, “coming,” in Latin, but Gerhard has the original Greek ἐπιφάνειαν, “appearing,” in mind. The authority to judge is clearly given to Christ as man, since Christ can only visibly appear to other humans as man, and not as God (rf. Col. 1:15; 1 Tim. 1:17; Heb. 11:27; John 4:24).

21 Estius, op. cit., p. 853.2.

22 Ibid., p. 854.1.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid., p. 853.2.

25 Ioannes Duraeus, Confutatio Responsionis Gulielmi Whitakeri (Paris: Apud Thomam Brumennium, 1582).

26 Ioannes Pistorius, Wegweiser für all verführte Christen (Ingolstadt: Andreas Angermayer, 1600). Gerhard cites this book as “hodeget.”, which is an abbreviated Latin transliteration of ὁδηγητήρ, a Greek word corresponding to Wegweiser in German. Pistorius’s father, Johannes Sr., was at first a Roman Catholic and then a Lutheran. Johannes Jr. went the opposite direction.

27 Rf. Iohannes Hentenius, ed., Ennarationes vetustissimorum Theologorum (Antwerp: In aedibus Iohannis Steelsii, 1545), folio 169, Caput Nonum.

28 Rf. Ambrose, op. cit. (endnote 11).

29 Estius, op. cit., p. 854.1.

30 Rf. H. J. Schroeder, trans., Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent (St. Louis and London: B. Herder Book Co., 1941), 18 (English), 297 (Latin), Fourth Session, “Decree Concerning the Edition and Use of the Sacred Books.”

31 Ibid., p. 41 (English), 319 (Latin).

32 Hentenius, op. cit. (endnote 27), folio 170. At the head of each section of Oecumenius’s commentary, Hentenius includes his own Latin version of the verses being treated.

Filed under Exegesis Tagged with 2 Timothy, 2 Timothy 4:6-8, Ambrose, Augustine, Basil the Great, Caesar Baronius, certainty, commentary, Cosmas Magalianus, Council of Trent, crown of righteousness, Cyprian, Duraeus, fight the good fight, Guilielmus Estius, Hentenius, Johann Gerhard, Johannes Pistorius, Oecumenius, polemics, rewards of grace, Theophylact, Vulgate, work-righteousness